For many years I’ve worked in this industry, and as I was going through the ranks from the trenches of being an apprentice, then a junior, intermediate, senior and last (but not least) a compositing and then a Senior VFX supervisor of a top tier VFX facility I could always feel and see that a huge hole existed in my own and many of my young coleagues education. Though we are all to a bigger or smaller extent very versed in the technical skills, I couldn’t help but wonder how does an artist that on the average has an above average eye for detail often miss something a supervisor can see as plain as the light of day. You know that feeling – how could I’ve missed that edge (or that telephone pole in the middle of a medieval set) – when a supervisor calls it out on a review.

I am positive 90% of the readers of this article had, and the rest surely will have a similar experience. But in time I have self-taught myself to gradually get better at this thing called VFX almost solely based on (here and there) failing to produce a finished composite and learning what does “finished shot” actually mean.

There are many big steps of the process of compositing a shot, and even more smaller ones in between them. The focus of this guide will be on the big steps as they always remain the same, while the in-between tends to be project/shot specific.

We will be splitting the process into several steps:

- Assessment

- Organization

- Review your work yourself first

- Review – further process

These steps are boiler plates holding the secret to good compositing practices. Master them, and you will have no problem applying your compositing skill in any and every software pipeline, company, no matter how big or small. So let’s jump right into the substance.

Assessment

Assessment is all about understanding what is it that needs to be done on your shot.

Once the shot is assigned to you, bring all your footage, foreground, background, CG, mattes, everything you are provided into your comp without worrying about where to put it. Just slam a bunch of read nodes in there. And then look through the sequences and stills, and start asking yourself (and your VFX supervisor if the answer isn’t obvious) following questions (listed questions are examples, there is always more – but that is all time-permitting).

- What’s your task?

- Do you have to key stuff?

- How much roto work awaits and is there a dedicated roto artist on the job?

- How much paint work awaits and is there a dedicated paint artist on the job?

- How much tracking work awaits and is there a dedicated matchmoving artist on the job?

- Do you have some amount of 3D projection work to be done?

- Is the 3D projection work on the foreground or on the background?

- Everything you can possibly think of, compositing related.

This is usually enough for not only figuring out where and what stuff will end up in your script, but also builds up a good starting point so you can involve yourself in the bidding process one day, when you acquire the necessary mileage to go through these questions in your mind in a matter of seconds or minutes right after reviewing the footage. Once you have to work on bids more often, you’ll find yourself doing most of these as default action.

All producers find out the easy or the hard way that a compositor usually gives the closest time-line assessment for delivering work, and these questions above are the reason why. It takes literally years of practice to be able to provide this kind of insight into Visual Effects and there is not a lot of experienced producers that would give an even approximate assessment of the work on his (her’s) own without our assistance.

This is an unusually over-looked but probably the most important step for doing an outstanding compositing job. So far, I haven’t heard of a single school program that focuses on this segment, and for me that’s like making people run without first spending time teaching them how to walk, or even crawl for that matter.

You can’t skip the basics, and in our line of work, assessment is the foundation on which your proverbial compositing house will be built.

Sometimes the work is handed down to you. Does that mean you should skip this step? Of course not. A good practice is to have a habit of always entering another artists script being fully prepared for the emergency build-it-from-scratch scenario and the number of good artists out there that share that attitude is ever growing. Sure, it’s just a precaution, and I doubt it has happened more than a handful of times during an artist’s career, but it has, and that’s enough for us to know to take it seriously.

So again. Review your footage, task-list, and anything you can think off before you actually do something.

Should you walk into another compositor’s script – assessment is very similar, reviewing all the footage it was brought into the script, understanding your task, asking even more questions (which parts of the script can I use – which I have to do from scratch – is any of the provided footage actually not used, etc)

You can (but you probably shouldn’t) skip this step on all other shots that fall into the same profile on the same show (same camera angle for example, in a conversation between characters), but you can’t skip it on similar tasked shots on another show. Different time of day, different camera, different footage, different scanner – always something different and enough to throw you off your assessment profile. So apply caution.

Organization

You know the answers to all the question you asked during Step 1. You understand the work at hand. What now? Well, let’s organize our script!

In step 1 (assessment) you have loaded all your footage into the comp.

Now you have to figure out a few things.

- Where to put the FG read nodes.

- Where to put the BG read nodes.

- How to setup your script or re-arrange a script that was handed over to you

In compositing applications an artist can design and structure his comp using a multitude of elements for script organization such as backdrops, dots, groups. In one of the most wide-spread compositing packages, The Foundry’s Nuke, a suggested and the most acceptable (due to it’s modular nature) way of organization of your scripts is a method referred to as “The Spine”, “The Tree” or “Vertical Script Flow” or whatever you might’ve heard it being called.

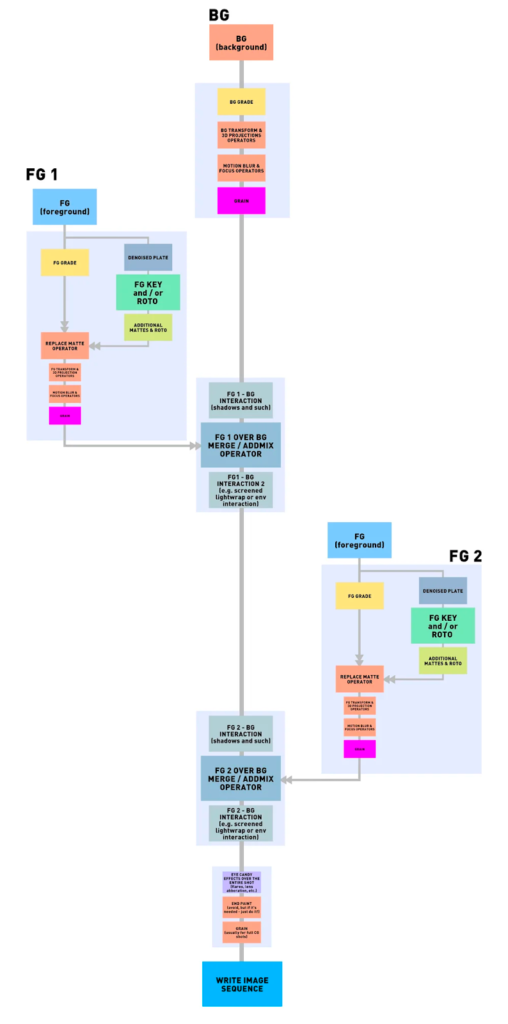

Diagram 1 shows an example of a pseudo-script with all the standard elements incorporated and designated through a system of BACKDROPS (text continues below the image).

We are layering our elements exactly inverse of how we would layer them in Photoshop or After Effects, as our “top” layer is actually at the bottom, right before the write image node.

[ A small update on the matter of the diagram: Pseudo-nodes I used are distributed with the purpose of giving you a general idea of the preferred node tree structure for production work-flow. However things often tend to play out differently show-to-show and shot-to-shot. Your paint nodes, your grain or your eye-candy effects, or just about any processing of the footage might happen before you merge them over the bg, or at the very bottom, or even in a pre-comp referenced into the master comp. It’s all relative and scalable. The diagram is solely here to support the idea of the script flow most commonly accepted in the industry nowadays. ]

Why do we prefer using this style of compositing?

So we can perform all our grade, tracking and focus work on each individual element, and having a smooth and easy access to assess the look of the comp as they are composited over the background. Of course. Why else you may ask? Nuke’s nodes are designed to take their input on the top of the node (by default) and to send their output on the bottom. Flame for example has the inputs on the left side and outputs on the right – hence the preferred flow of a Flame batch is left to right, but the same logic does still apply.

Review your work yourself first

Once your shot is comped – Look at it. Play it. Then play it again. And again. Think about everything that’s wrong with your shot.

- How are the edges?

- How’s the tracking?

- Does your FG live in the same world like the BG (color-wise)?

- How’s the grain?

- What do you think your VFX supervisor will have comments on?

You have to scrutinize everything about your work. The harder you are on yourself, the closer you are to deliver outstanding work. Play the heck out of your shot – BUT not for an entire day! Play it when you’re in a somewhat happy place, close to your goal, but respecting your assessed or given dead-line. To review your shot make sure you watch it under different visual circumstances you will adjust yourself (Nuke is a great tool for that):

- Gamma it UP

- Gamma it DOWN

- Look at it under the show LUT

- Look at it under different LUT’s

- Go up a few or many stops

- Go down a few or many stops

- Stare at each individual channel, R, G, B, Luminescence, Alpha

- Look at both individual frames standing alone as pictures, but also play it. A lot.

Your task as a compositor is relatively simple in the end – every single channel has to integrate well and not break under ANY of these forced tweaks that still might never be what your shot will look like in the end after final color work is applied.

Today we are being constantly asked to provide mattes for our shots to assist in DI grading process. Some will argue the mattes for grading purposes might have to look different than the mattes we actually used to comp our shots, due to the nature of the DI process. I am sharing an opinion with many colleagues that you should take the matte you are using to composite the shot, and than Grade your shot and see how fast is the edge quality going to break when you start cranking the BG exposure to extreme leveles. If your matte holds for several full stops – your matte will be fine.

Review – further process

After reviewing the work yourself and your internal review the shot will go to the “big reviews”. Usually the first step on the “stairway to final” you have to overcome is internal review with your team’s VFX supervisor, then another one with your project’s VFX supervisor (usually hired by the client – production of the feature or the ad agency) and in the end with the client himself (feature director, executive producer or lead agency creatives).

The artist is not only doing the shots, he is also often heavily involved in the process of internal reviews. That means that our shots are heavily scrutinized in sessions in the theater by the VFX supervisors, other artists, producers and often an even wider array of people such as cardiologists, children, girlfriends, boyfriends, janitors, etc… Everyone is usually encouraged to give an input because the more eyes see the work, the more flaws in the work can be revealed. Being honest about other artists work and your own, is part of being a solid artist and a team member with a strong smell of team spirit. So be prepared for everything that comes your way, and leave your ego at the front entrance to the building. Being open to taking feedback no matter where it comes from actually helps develop client handling skills and you should always pay attention to feedback – you never know who will see something no one else has!

Conclusion

This industry has become very technical. We are all painfully aware that the Art side of the Art of Compositing and all of Visual Effects had been somewhat removed out of the lime-light though it is sometimes the main driving force of a successful Hollywood block-buster. A lot of laymen observers – due to media and even educational institution’s emphasis on the advancement of the software, hardware and all the beautiful new tools we are frequently being provided (all meant to cut the working time) – forget that compositing is an Art and that all the technical knowledge can’t help you understand what is, actually, a beautifully finished VFX shot. It’s time, attention to detail coupled with constant development of your technical skill-set that makes one a master, not a set of powerful tools and plugins.

You can and you should organize your workflow and you can and you should make yourself as efficient as possible, but you are doing all of that so you can focus on the Art itself and make the beautiful images to wow the crowds all over the world. It does now, and it will in many years in the future, take an artistic eye and attention to many little nuances of compositing to create truly beautiful images we do. Whether it is a 2D, 3D or a holo-feature – there will be a need to make things look more beautiful than the actual on-set photography allows. We are not a button to be pressed that delivers finished product the industry is trying to make the laymen believe, but a helping, loving and hard-working hand that brings the imagination of the story to the screen and puts it in front of the audience making people fall in love, tremble in fear, or believe aliens are walking among us.

A VFX artist should always remember that visual effects are a group effort, but a group effort of individuals each providing their unique input and working together towards a common goal. You are important no matter where you go on the credit roll and no matter how “low” or “high” the level of the work you were tasked to do was. Don’t break under the chatter of the VFX artist forums on-line. Some of that is really depressing to read, misleading and often defeatist, but they always will be simply because the majority of people that have the time to regulate them usually have too much spare time on their hands anyway. Look for resources that are useful for your personal workflow and career development.

Do your work knowing that though the perception of the public may claim otherwise with directors and production-side VFX supervisors taking most of the glory and credit for your hard work – in the end it is your work that will end up on your showreel to showcase your art to others interested in hiring or just admiring your golden VFX hands.

So – make your work count – and make it beautiful!